The interconnectedness of communications, architecture, and organisational design

Photo by John Barkiple on Unsplash

Photo by John Barkiple on Unsplash

CEO of Amazon, Jeff Bezos famously once stood up to the suggestion that employees should communicate more with his retort “No, communication is terrible!”.

I was reminded of this recently while reading the book Team Topologies which recommends that architectural and organisational designs should leverage the high-bandwidth communication that is natural within teams and minimise the low-bandwidth communication between teams. Jeff Bezo’s sentiment was similar — he recognised that organisations often find themselves bogged down in cross-team communication to co-ordinate complex work. His desire to eliminate this kind of communication manifested itself most clearly in his (in)famous 2002 API mandate which dictated that all Amazon teams must communicate with each other through formalised APIs.

This single email is widely regarded as one of the most important contributors to Amazon’s commercial success building AWS. The technical architecture that emerged as a result of that mandate — one of many loosely coupled services with well-defined APIs — mirrored the organisational structure that was created by that email and helped Amazon become the defacto cloud for the new generation of garage start-ups. This is an example of what’s known as Conway’s Law, first expressed in the 60’s by Melvin Conway:

“Any organisation that designs a system … will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organisation’s communication structure”

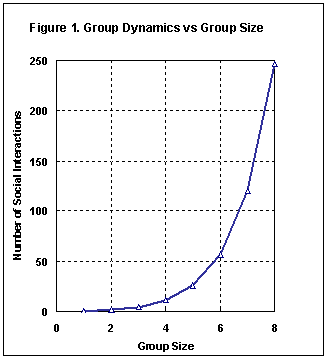

So, if communication within teams is good and between teams is bad, bigger teams are better right? Unfortunately, the answer is usually no. Research by psychologist J. Richard Hackman, bluntly stated, “Big teams usually wind up just wasting everybody’s time.” What Hackman found is that a team’s performance is correlated with the number of connections between people in the team, and those connections increases rapidly as the team grows. This isn’t something new to software engineering, in the 1975 book Mythical Man Month Brooks’s law was coined which states that: “adding human-power to a late software project just makes it later.” An experience most of us are probably all too familiar with.

I’m sure this is something many of you feel instinctively — there’s quite a narrow size range where a team feels right and flies, which is essentially down to our human psychology. A 2006 paper by David Snowden lays out three numbers that have direct relevance to team relationships: 5 as the effect limit of the short term memory, 15 as a natural limit on deep trust, and 150 (the Dunbar number) as a natural limit on acquaintances. We can’t beat these numbers — our organisational design has to recognise and work around these psychological limitations.

This is where another Bezo’s rule comes in — that no team should be larger than what two pizzas can feed, which is a catchy way of reframing the rule of thumb that has emerged from the world of agile development that the ideal size for development teams is around 7 people plus or minus 2. Importantly, the [agile movement advocates](https://scrumguides.org/scrum-guide.html these teams should be cross-functional:

“Scrum Teams are self-organizing and cross-functional… Cross-functional teams have all competencies needed to accomplish the work without depending on others not part of the team.”

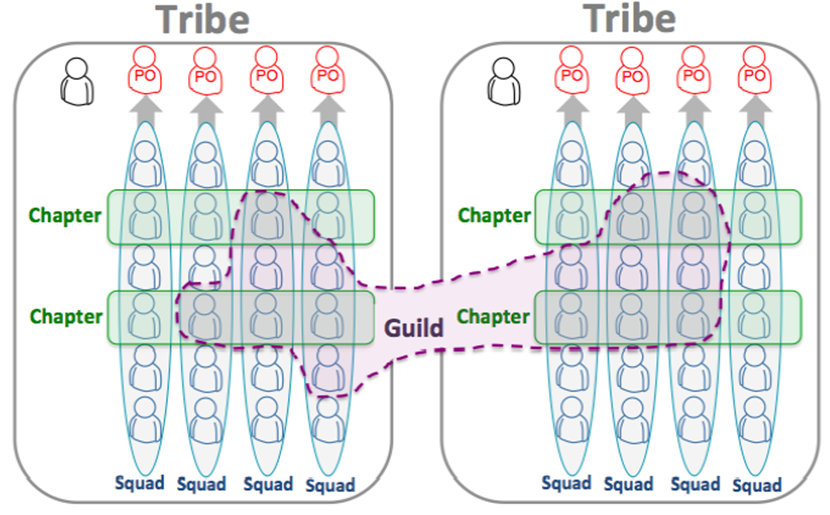

This is another recognition that the necessary communication between teams in a functional model is difficult, and so agile recommends a team structure which internalises that cross-functional interaction. The 2012 publication of the Spotify model popularised this for a new generation of agile organisations with its model of cross-functional squads being the primary team, and functional chapters being the matrix management.

More recently the DevOps movement has been all about breaking down organisational silos perpetuated by poor communication paths — if you want a DevOps culture, don’t have a Dev team and an Ops team! This use of organisational design to drive the culture and architecture you desire was given a name in 2015 by Thoughtworks when they suggested that organisations should hack Conway’s Law:

“The ‘Inverse Conway Manoeuvre’ recommends evolving your team and organizational structure to promote your desired architecture. Ideally your technology architecture will display isomorphism with your business architecture.”

Redgate has had small cross-functional product teams for a long while. We’ve been successful because our organisational design has been well suited to building a portfolio of largely independent end-user tools. But as we evolve into an era of bigger and more inter-connected enterprise software, our organisational design and software architecture need to work in concert to meet the challenges ahead.

For the first time we’re creating software architect roles to help us map out internal boundaries in our products that can not only reflect technologies and business domains, but also are right-sized for the cognitive capacity of small product teams and optimised to reduce the need for cross-team communication. We believe, if we get this right, our engineering operating model will scale with our software architecture and our organisational design supporting rather than fighting each other.