Designing an engineering distribution model to fit your go-to-market

While many may proclaim that there’s one true way to distribute modern software, the reality is there is no single distribution model that suits every need. You may decide to ship software appliances in VMs and containers, utilise mobile app stores, build multi-tenant SaaS, open source your product, or provide on-prem downloadable airgapped installs. In the real world, software distribution models vary significantly according to the needs of go-to-market strategies.

Although a lot of the discussion about distribution focuses on which approach has the lowest unit economics, this isn’t the only constraint for most businesses. There are other forces that can be just as important:

- What kind of onboarding experience is needed? — A small number of enterprise customers supported by professional services, partners and resellers is very different customer journey to the automated low-cost onboarding of high volumes of self-service b2c customers.

- Is portability important, do you need to support diverse infrastructures across multiple clouds, self-hosted, on-prem?

- Are there compliance concerns driving customer isolation, data sovereignty requirements, and legislatives constraints?

- Is proximity to other infrastructure important — do you have to be close to data or compute or fit into an existing ecosystem?

- Are you affected by workforce geographies, multiple offices, subcontracted dev teams?

- Is the use single user, collaborative, or supporting multiple personas and multi-channel?

- What’s the chronology of usage — Is the product task oriented or transformational, is it an everyday carry or sporadic use?

- And so on…

The bottom line is that when designing an engineering operating model, and in particular it’s modes of software distribution, we need first to understand the go-to-markets the business wants to execute — an engineering function trying to be great at every distribution model is a recipe for mediocrity, a business strategy that isn’t aligned to engineering’s design is not playing to its strengths. It’s a focused partnership…

We have to mindfully design engineering to deliver the needs of the business strategy, and the business strategy has to exploit what engineering is designed for.

Redgate’s early success was built on a foundation of delivering ingeniously simple products directly to end users. Initially sales were inbound, driven by Adwords, content marketing, and word of mouth. Building a large user base for our tools generated widespread brand awareness and positive sentiment to Redgate in the market. Our engineering distribution model was simply the provision of downloadable installers to support a self-service download-try-buy business model. Life was simple back then.

As we moved beyond the single user to sell to teams, the commercial model evolved introducing tiered discounts and bundles to create an upsell model to drive whole team adoption. Engineering had to implement more complicated multi-product installers, and we started to introduce on-prem client server systems and peer to peer models into our portfolio.

In more recent years we’ve added solution selling to create a path from the team to the whole company. Our products now work together to solve a higher value business problem. Purchases are often part of transformation or change projects which require proof of concept, partners, and resellers. The commercial model has evolved again to build an outbound account sales function to support solution selling. The product is the portfolio, the customer is the organisation.

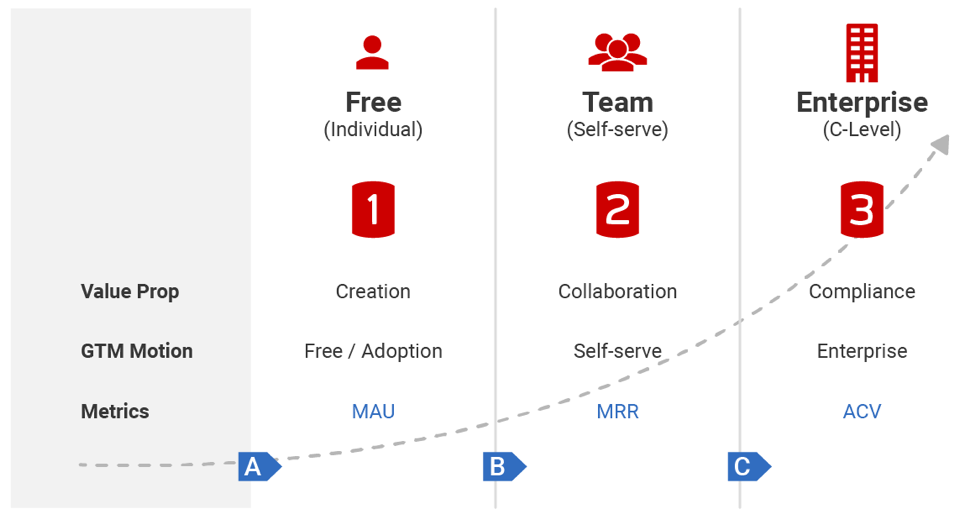

Redgate’s business has evolved over the last 21 years from our roots in a simple inbound model, to today’s integrated system where a tool in the hands of an end user leads to team usage and finally to an enterprise procurement. Internally we’ve adopted the vernacular of Adam Gross’ 1–2–3 framework to articulate this approach, you can hear him talk about it in more depth on Heavybit.

For engineering, the 1–2–3 model is not just a commercial model, it’s the framing we use to think about our software distribution needs at each level. Looking to the future, our technical strategy is pushing a number of fronts. For individuals we’re still going to be supporting a lot of downloads, but increasingly we’re packaging our tools into containers for distribution and with Flyway joining our portfolio we’re exploring the role open source and open core can play. In the teams arena we’re seeing on-prem client server models continue to decline as customers move to the cloud and the desire to invest in multi-tenant SaaS distribution for future products.

But by far our biggest current investment and focus is in creating a Kubernetes-based platform which can deliver portability, compliance, and portfolio integration for our enterprise customers who are buying Redgate (mode 3 in the model). Our platform strategy is the result of engineering looking ahead to where the business strategy is taking us over the next five years as we open up the enterprise market, anticipating the distribution model that will be needed to get engineering Enterprise Ready.